In Christmas time, Australia is undergoing its ordinary policies of migrants detention at Christmas Island. Refugees and forcibly displaced detained in those contemporary concentration camps face moral dilemmas from which we could learn of. Pardon could be a valuable lesson for democracies.

In that time of the year, an important part of the world is celebrating Christmas. Not just in what is called the ‘occidental countries’, but in all over the world where there is Christian minorities. Yet this text won’t be about this Christmas celebration, but on another Christmas subject: Australia’s Immigration Detention Center in its Christmas Island at the Indian Ocean and which moral lessons we can learn from it.

With the Fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) the world was looking at what people believed to be a prominent moment of peace in the international scenario. Today, 25 years later, the anniversary of the Wall Fall was celebrated in November 9th with the event Lichtgrenze[1]_ (wall of light) organized by Kultur Projekte Berlin and other associations in the city of Berlin. Their main purpose, with its evanescent enlightened balloons’ wall, was to show a “symbol of hope for a world without walls”_[2]. But why does it matter? -Surely because we do not have seen a time of peace and union after 1989, but instead a time of rising and multiplying walls all around the world. Walls that divide territories and individuals in ‘have’ and ‘have not’ rights; walls to counter immigration and vulnerable people willing to flee their countries for an uncountable number of reasons.

On denying equal rights and dignity of life conditions to immigrants, democracies deny its own political fundaments and become partially responsible for the lives of those trying to reach their territories. In Europe and Australia, for example, the push-back operations, which consist in leaving vulnerable migrants perish by sending them back into a violent environment or even letting them die in international seas, have been a common and shameful political act practiced by democratic countries. Indeed, these political decisions are not just against democratic principles but it also contradicts many international law conventions. It namely disregards the effort made by the international community to protect refugees and statelessness people under the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol, and the 1954 and 1961 Conventions on the Status of Stateless Persons and the reduction of Statelessness, all grounded in the article 14 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of human rights[3]_. It is thus clear that democracies are responsible just as civil wars from non-democratic governments, systemic famine and poverty, and environmental crisis are on the irregular migrants’ misery maintenance. The question of why are democracies incapable to fulfill its political obligations is an important one that I do not intend to analyze today. Instead, I will focus on the moral dimension of politics lived by millions[4] of migrant survivals of natural and social disasters, oftentimes inhabiting contemporary concentration camps.

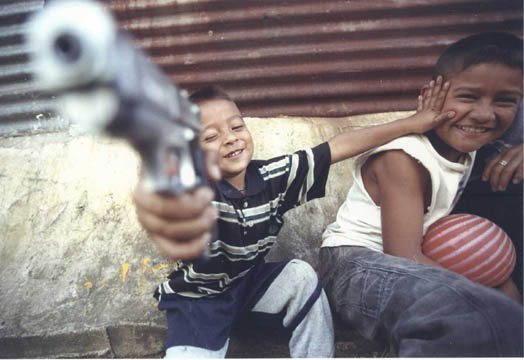

Dadaab, Melilla, Maheba, Boreah, Kountaya, Bo-Kenema, Kailahun, Bong, Monrovia, Balata, Askar, Kuankan, Tinzaoutine, and Christmas are a few refugee camps existing nowadays with very impressive proportions. Almost all of them correspond to at least a medium sized European town[5]_. They are complex legal spaces surrounded by a legal void in all its levels. For example, it is not rare to have refugee victims of civil war crimes cohabiting with ancient violence perpetrators that have not been taken to court. This legal gap constitutes one of the very tough dimensions implied in dealing with human forcibly displaced through concentration camps and the lack of structure imposed by international indifference. However, refugees have shown their capacity to rebuild their lives and confront these enormous difficulties resolutely, removing themselves out from a victimization frame.

The important ethnographic research made by the French anthropologist Michel Agier (published in English 2010, Managing the Undesirables) during 2000-2007 investigates this question. In an interview made at the Kuankan’s camp in Forested Guinea with a young refugee girl of fifteen years old arrived from Liberia, Agier reports: “her dad was murdered; then she was captured by an armed group of Taylor’s force; another LURD attack had place and her kidnappers escaped; at that time her mother disappears; she is then retaken by an armed group of Taylor’s force; she is obliged to carry weapons and to fight under threat; but she refuses to fight; the soldiers grab, abuse and torture her (she shows the traces on her body); she asks pardon to the soldiers; then she is raped by four men; she manages to escape in the next LURD attack until be found by a representative of Kuankan’s camp.”[6]_ Taking this narration as an example of what many women might had to endure in Liberia’s war, and acknowledging the further constant will for forgiveness expressed by Liberian refugees[7], we see that they are not just victims, but political actors. With their pardon they want to forget times of war and forgive delirious worriers, but above all restore the order in their country.

The pardon showed by refugees in such extreme situations, as a way of forgiveness and forgetfulness (amnesia for amnesty) constitutes a political and normative act — therefore not a psychological fragility. In a time in which democracies fail to pardon irregular territorial entrances and condemn not guilty innocents by something they had not deliberately undergone, refugees and forcibly displaced migrants teach us how to forgive the unforgivable. Isn’t it time for democracies to learn how to amnesty irregular migrations for the sake of democratic principles? In the current case, the moral act of pardon constitutes an important political act for democracy strengthening. If nothing changes, we will need to beg their pardon in the future as well.

[1] More information can be found at: http://www.spiegel.de/video/mauerfall-feier-in-berlin-lichtgrenze-steigt-auf-video-1534673.html

[2] http://www.berlin.de/mauerfall2014/en/25-years-fall-of-the-wall/

[3]http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html#_ga=1.191653290.1820769779.1417424767

[4] 51.2 million is the number of forcibly displaced worldwide by the UNHCR for 2013. The number is in rising and it does not take into account all the unreported displaced.

[5] Dadaab alone counts with more than half a million inhabitants.

[6] AGIER, M., p. 244-246 french edition (Flammarion 2008).

[7] See note 6.