The Nubians, Egypt’s invisible people: Removing a nation through neglect and assimilation

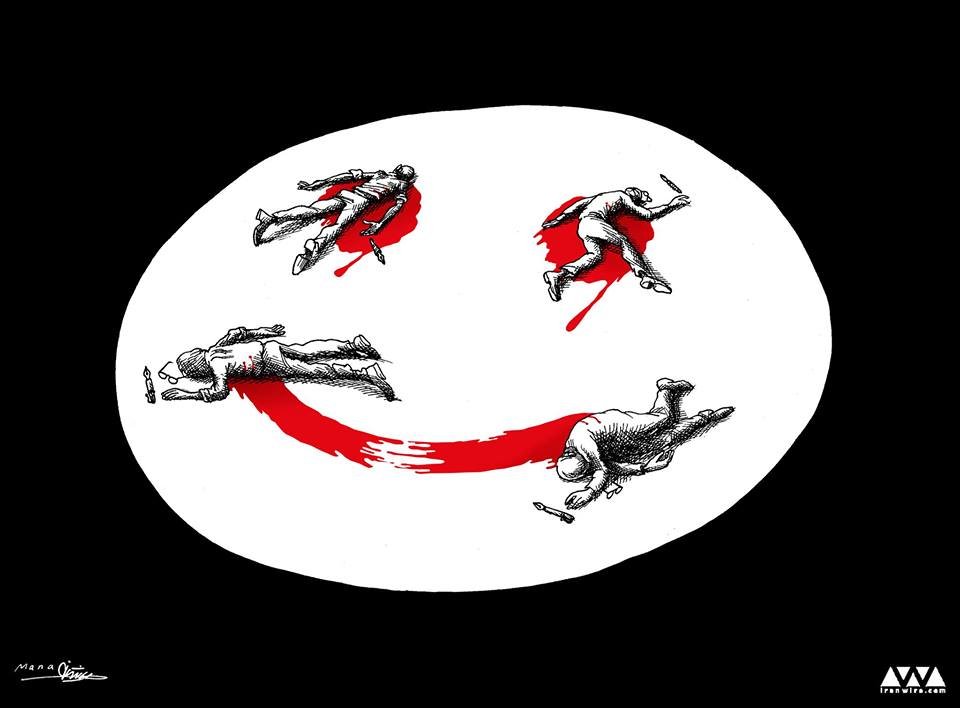

In contemporary media, it seems impossible to avoid buzzwords like “human rights” and “violations” or to see pages upon pages of reported violence and death. It is no different in Egypt, as the country continues to struggle with both internal and external conflict. But in the midst of all the violence, voices are also silenced. How can a country progress beyond what it has known, if it refuses to acknowledge and recognize all of its people and their history?

EGYPT… When the name is uttered, various associations can be made that may link one to its ancient history filled with pyramids, pharaohs, and hieroglyphics or to its contemporary political situation with respect to the Arab Spring and international human rights. What are generally lost among these associations are Nubia and the Nubian people.

Once a collective community of 44 villages, Nubians covered an area of approximately 78,000 acres on the banks of the Nile in southern Egypt [1]. However, with the construction of the Aswan Reservoir, which preceded the High Dam, Nubians were forced to relocate multiple times in 1902, 1912, and 1933 [2]. Although the government approved the Nubian’s selected destination for relocation along the Nile, the erection of the High Dam in 1964 forced the Nubians to move, yet again, from their homeland in order to make room for Lake Nasser. Although many Nubians have acknowledged the necessity of the High Dam for the benefit of the country, the main source of discontentment and pain is rooted in their invisibility both in Egyptian history and contemporary Egypt.

Between December 28th, 2014 and January 15th, 2015, in a collaborative effort made by CISV Egypt [3] and Partner Organization, Fekra El-Shallal Cultural Center [4], an International People’s Project was held in Aswan where participants from different countries came together to work with the local community. One of the projects sought to document the Nubians with respect to their lives, experience with internal displacement, and culture. Through the interviews, the Nubians residing in Heissa Island, Kom Ombo, and West Aswan adamantly reiterated two main themes: the need for cultural preservation and the concept of identity with respect to the greater context of Egypt. Regardless of whether the individual had personally experienced displacement, it is evident through their words and silence that each of their lives has been impacted and the struggle continues.

The longevity and survival of any society is linked to their understanding of identity and rooted in cultural preservation, which includes but is not limited to the people’s history, language, music, art, traditions, and customs. In thinking through cultural preservation, it is interesting to see how the interviewees identify themselves as either Egyptian-Nubians or Nubian-Egyptians. The distinction between listing either their Egyptian or Nubian identity first is important as it illuminates how each individual understands nationality. Interviewees, who identified themselves as Egyptian-Nubian, understood themselves to be part of the greater context of Egypt with strong roots to the regional Nubian culture, whereas those who identified themselves as Nubian-Egyptians understood their nationality to be Nubian but their citizenship (official legal documents) as Egyptian.

Regardless of age and gender each interviewee understood hers/his role as being linked to the greater context of Egypt while simultaneously possessing a strong sense of pride and desire to sustain and teach others of their Nubian identity, which has been scarcely documented within the Egyptian history. References to Nubia are limited and usually revolve around their ancient history, salvage of monuments or the construction of the High Dam and Lake Nasser. The Nubian people, their traditions and contemporary position within Egypt have been omitted, oversimplified, or reduced to tourist attractions. Take for instance, the Nubian Museum in Aswan [5]. Although it is organized and informative, there are no references to contemporary Nubian people after their experiences with internal displacement. The museum merely documents selected accounts of ancient Nubian history with respect to the displayed monument fragments and artifacts, and the excavation and preservation efforts of UNESCO and affiliated parties – a theme that is reiterated on the museum website.

The documentation and exhibition of ancient Nubian history and of scattered monument fragments and artifacts are not enough. As expressed by nearly all of the Nubians interviewed, schools neither teach nor reference the role of Nubians in ancient or contemporary Egypt. Similarly, there are two dialects of the Nubian language, which have been taught to each generation through oral traditions. However, with Arabic as the official language of Egypt, the Nubian language is slowly coming to extinction, as it is neither taught in schools nor used outside of the Nubian community.

Furthermore, with multiple displacements, the Nubian community that was once a collective is now broken into smaller tribes that reside in modern day Sudan and Egypt. For the Nubians living in Aswan, many have relocated to areas that are far from their original source of livelihood, the Nile. As a result, many are forced to migrate to urban cities like Cairo and Alexandria for work, which further exacerbate and hinder cultural preservation. For purposes of adaptation and survival, assimilation into the greater Egyptian context has stifled their ability to reproduce and sustain their cultural identity. Nubian traditions such as arts and crafts, music, and customs suffer from the same affliction of potential extinction.

Since the construction of the High Dam in 1964, Nubians have been voicing their demands for their rights to return and own their land, to have their culture and identity be recognized and acknowledged nationwide, and to receive proper compensation. As Egypt underwent changes during the 2011 “revolution” it seemed hopeful that some recognition and acknowledgement might be within reach in the following years. In October 2014, a new committee was formed and headed by the Ministry of Transitional Justice, Ibrahim El-Heneidy and included Thomas wa Affia, the head of one of the largest Nubian tribes and other public figures and lawyers from the Nubian community [6]. However, earlier this month, February 2015, after only five months of resubmitting their requests for the right of return, the Egyptian government has refused their demands; thus, leaving the situation at standstill.

The desire and need from the Nubian people to record, preserve and sustain their nationality and culture should not come as a surprise. Without records, preservation and sustainability of a culture and people would be impossible and with it, the Nubians would cease to exist. To the international community it may seem that Egypt is slowly making transitions towards becoming a more human rights-oriented and “democratic” government and society. But what kind of future can be expected if the government continues to ignore a vital part of its country’s history and people? By neglecting to recognize and acknowledge the role and rights of the Nubians, the Egyptian government is slowly erasing them from existence as their language, culture and traditions continue to fade away through neglect and assimilation, which vaguely resembles the fate of Native Americans in the U.S.

What is apparent through the Egyptian media through news channels such as Al Masry Al Youm [7] (or the English version, Egypt Independent [8]), Mada Masr [9], Egyptian Streets [10], Ahram Online [11] or Daily News Egypt [12] is the government’s focus on fighting “terrorism” within the country, international relations, religion and its various manifestations, and music, art and culture. This is not to say that the plights of the Nubians are to be compared as being more or less important or significant, but to understand a country means to also understand its people, their history, culture, and role.

In closing, I propose the following questions. As contemporary societies continue to move “forward” by supporting agendas that are relevant to a selected group of people, is it inevitable that smaller groups will be overlooked or potentially eliminated in the process, whether through assimilation or negligence? If this is the case, what does it suggest about contemporary society and politics? What then, is meant by “progress”; how do we define and measure “progress”? Is it simply through international relations or only through statistics and figures regarding the domestic legislation in accordance to international regulations, perceived gender equality, poverty and education ratios, and economic security? Lastly, what does this suggest about the concept of “rights” and “justice”? If rights and justice are only available to a selected few where the rest are silenced or overlooked, are we still pursuing human rights, or merely manufacturing a concept?

[1] Aman, A. (2014). Egypt’s Nubians demand rights on Aswan high dam anniversary. Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East.

[2] Noshokaty, A. (2013a). Egypt Nubia: 50 years of displacement. Ahram Online English.

[3] CISV. (2015).

[4] Fekra El-Shallal Cultural Center. (2015).

[5] Nubia Museum. (n.d.).

[6] Egypt forms committee to draft law for Nubian resettlement. (2014). Ahram Online English.

[7] Al Masry Al Youm. (2015).

[8] Egypt Independent. (2015).

[9] Mada Masr. (2015).

[10] Egyptian Streets. (2015).

[11] Ahram Online. (2015).

[12] Daily News Egypt. (2015).