The liberal intellectual class often suggests that the violence perpetrated by the Islamic State is unique in its scope and barbarism. This rhetorical framework subtly suggests that the violence of Western governments is shaped primarily by ethical considerations. Accepting this discourse ignores the primary outcome of US military innovation: state perpetrated violence that is unrestricted spatially or temporally.

Text by Evan Sandlin

The first five pages of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison describe the 18th Century torture and quartering of Robert-Francois Damiens in brutal and gruesome detail. Foucault then asks a simple question: why do societies no longer punish transgressors in this manner? The conventional answer assumes that human moral and ethical progress has led to the adoption of more humane methods of law enforcement and state-sanctioned punishment. Foucault is critical of this answer, and gives an account of how the modern penal system developed primarily from innovations in the art of subjugation rather than ethnical concerns.

Yet, the conventional answer still dominates political discourse in numerous policy realms and is especially present in discussions of the US “War on Terror.” A recent article in The Independent frames the horrors of the Syrian civil war as an example of a “loss of humanity” among the combatants, most notably the Islamic State (ISIS). The torture, the beheadings, and the crucifixions perpetrated by ISIS and similar militant groups are deemed incompatible with Western morality. The most recent transgressions, including the execution of 21 Egyptian Christians and the burning alive of a Jordanian fighter pilot, elicited widespread shock and disbelief that any political organization could embrace methods so seemingly out of place with modernity. Like Foucault’s description of the execution of Robert-Francois Damiens, those reading reports of ISIS atrocities cannot help but find themselves appreciating their own moral superiority and being thankful that the political unit to which they belong does not inflict such brutality on the battlefield.

This framework is rendered incoherent by the lack of consistency between the discourse of the state, its actions, and the actions of its allies. ISIS is no match for the United States when it comes to sheer destructive capacity. The US killed 20,000 civilians in the first few months of the Iraq war, whereas ISIS has killed perhaps a quarter as many in the last 6 months. Critics may point out that it is the methods rather than the capabilities of ISIS that make the group exceptionally barbaric. However, US partners and allies use similar methods. In 2014 Saudi Arabia beheaded upwards of 60 people, with foreigners accounting for about half of that number. It is also difficult to seriously make the case that incinerating human beings with hellfire missiles fired from an American drone is truly less barbaric than burning a human to death with gasoline.

If the methods of warfare the US has chosen do not strictly correspond to moral and ethical advances then for what reason have these methods been adopted? For Foucault the state’s embrace of the penitentiary over public torture bolstered state power and remedied problems that emerged from the latter form of subjugation. Heavy-handed tactics in the public eye can produce unintended consequences. The torture and execution of enemies of the state made the victim’s body a site of sympathy, relocating guilt to the executioner and producing tension between the sovereign and its subjects. The penitentiary is a more sophisticated form of subjugation that became possible due to technological advances. It produces docile subjects and renders them largely invisible to the population at large, who are reassured that the guilty are receiving fair and just punishment. The state was therefore able to ensure obedience without the negative externalities that resulted from the use of graphic public violence.

Like domestic law-enforcement, the procedures used in the foreign policy realm result from technological and methodological advancement in the art of violence rather than moral concerns. The US has been able to effectively neutralize enemies without producing or exacerbating internal cleavages. Technology has been fundamental to this task. Gravity bombs and napalm have been replaced with guided bombs and hellfire missiles. The innovation has the effect of making violence more discriminant, allowing the US the ability to produce terror in its foreign subjects while keeping that same terror largely hidden from or accepted by its domestic constituency. Advanced weaponry, rather than slowly killing through burning or maiming, completely destroys bodies. Survivors of drone strikes report only finding pieces of the dead. In instances when the identity of the body parts has been rendered indiscernible survivors of US terror have to “collect pieces of flesh” that may or may not belong to their deceased relative’s and “put them in a coffin.” Like the penitentiary, which renders the bodies of the deviant invisible, so to do the hellfire missiles of a drone render the bodies of the other unseen. In disgusting irony what is touted as a humane advance in warfare has enacted the most extreme form of violence upon the body.

Advanced warfare has not only allowed the US to enact violence with little consequence but also expanded the spatial and temporal dimension in which this violence is applicable. Drone warfare has expanded the US campaign of terror to virtually any area of interest without imposing significant physical presence. The discriminate nature of the campaign also obscures the temporal presence of warfare. Long bombing campaigns that entail visible physical military manifestation remove any illusion of “peacetime” and provoke domestic discussions on the appropriateness of such action. Periodic US initiated assassination by air occupies a much more limited immediate space and time, more reminiscent of a law-enforcement action. Again, the motivation for these innovations is primarily the enhancement of state power rather than ethics, and what is considered moral improvement actually sanctions a vast expansion of state violence.

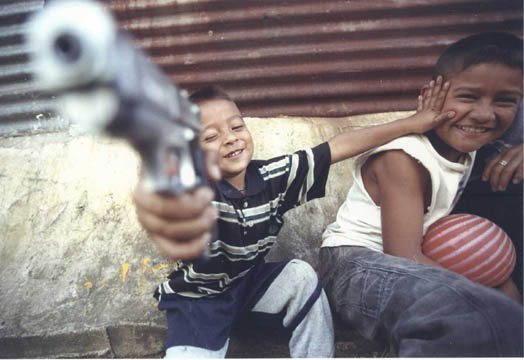

The US utilizes advanced weaponry that allows it to enact extreme violence without producing adverse internal penalties. Likewise, ISIS resorts to brutal public executions and extreme torture for political purposes, albeit different ones. In an area of the globe where internationally recognized government is more or less absent legitimacy is granted to those able to inflict the most violence. The graphic executions of Western citizens are meant to induce a military response from the US and its allies, which they have obliged. The Western-Arab military campaign is advantageous for recruitment purposes, as those who perceive the newly anointed Caliphate to be suffering from military attack will be further convinced of its legitimacy and the necessity to come to its defense.

Investigating the underlying motivations for the violence emanating from both ISIS and the United States is in no way an attempt to erase any moral distinctions between the two. There are other ways to distinguish actors apart from the methods they use to achieve their goals, such as the goals themselves. However, the moral outrage emanating from the US liberal intellectual community at the methods used by ISIS dangerously validates US approaches to maintaining ceaseless inconsequential violence under the banner of compassion. Like the discourse surrounding the development of the penitentiary described by Foucault, the discourse surrounding US warfare only enables state violence and produces domestic obedience instead of the resistance it should inspire.

Evan Sandlin received his bachelor’s degree in Political Science from California Lutheran University and is currently a PhD graduate student in the UC Davis Department of Political Science. He currently is conducting research on the political motivations behind US economic aid allocations and on the consequences of US military intervention.