Conquering its independence in 1966 from the United Kingdom, Guyana remains a forgotten country in South American political mainstream. While the most part of South American countries present a considerable progress on school enrollment and adult’s illiteracy reduction, Guyana stands at the top of non-school enrollment and adult illiteracy: it has an impressive 572% bigger rate of out-of-school children than Brazil for a 26187.9% smaller population. A common project of a stronger regional political cooperation among South American countries would very likely be profitable to Guyanese domestic scopes and constitutional legal premises. It could be argue that being a country in the Caribbean region, the national de facto detachment from South America would be strategical. We want to show the reasons for this detachment, why it is not strategical, and unveil the colonial roots of this antiquate practice.

Text by Arthur Catraio

Conquering its independence in 1966 from the United Kingdom, Guyana (anciently called British Guiana) remains a forgotten country in South American political mainstream. In effect, the terms usually used as Latin America or Ibero-America to refer to regional policies in the continent conceptually exclude the country of the region, being one of the two non-latin countries of South America, together with its neighbor Suriname. It could be argue that being a country in the Caribbean region, the national de facto detachment from South America would be strategical. We want to show the reasons for this detachment, why it is not strategical, and unveil the colonial roots of this antiquate practice.

The Guyanese society has inherited through history a very diverse population of nations, composed mainly by East-Indian and black Africans, and in a smaller proportion by native ethnic cultures and European descendants. While most of the black Africans were brought to the region by the Dutch Empire as slaves during the period of the transatlantic slave trade, East-Indian immigrants were brought lately with the British conquest between 1838-1917. Based on a colonial economic model, the former group was originally responsible for exploiting mineral natural ressources (eg. gold), while the last was in charge of Sugar cane production and massive rice cultivation (characteristic of Asian culinary), formalizing the well known colonial system of basic production for exportation towards metropolitan regions.

A rivalry between those two largest ethnic groups were therefore created in an economic competitive environment for productivity towards exportation by the British and Dutch strategy of colonialism. This rivalry is still present nowadays, and it represents the main source of disagreement in the national political scenario, in which the ruler party People Progressive Party/Civic (PPP) is composed by an East-Indian ethnic majority while the second biggest party, A Partnership for National Unity (APNU), is composed by a black African ethnic majority. It clearly represents the persistence of an inherited inappropriate historical model of politics to contemporary democratic institutions. However, even if an ethnic dispute still exists at the political level in Guyana, the proclamation of its Republican Constitution marks a very important step into the democratic project.

Later to the proclamation of the first Republican Constitution in 1966, enacted through the Independence Act passed on May 1966 [1], the national political history of Guyana led the country to a new Constitution on February 1980 which has been since then the ground principle of all national rights. In this article, we will pay specially attention to the legal provisions regarding the basic right to education and its importance for the national democracy. In the Preamble of the 1980’s Constitution, it is stated that:

“WE, THE GUYANESE PEOPLE, … Acknowledge the aspirations of our young people who, in their own words, have declared that the future of Guyana belongs to its young people, who aspire to live in a safe society which respects their dignity, protects their rights, recognises their potential, listens to their voices, provides opportunities, ensures a healthy environment and encourages people of all races live in harmony and peace and affirm that their declaration will be binding on our institutions and be a part of the context of our basic law.”

The persistent remark on the ‘young [Guyanese] people’ defines as a national priority and interest the protection and participation of young people inside the national political life, and for this reason the right to Education becomes a pivotal fundamental principle for any agenda of domestic policies. It can reasonably be sustained under the articles 27 and 38E of the Constitution:

“Article 27.

1.Every citizen has the right to free education from nursery to university as well as at non-formal places where opportunities are provided for education and training.

2. It is the duty of the State to provide education that would include curricula designed to reflect the cultural diversities of Guyana and disciplines that are necessary to prepare students to deal with social issues and to meet the challenges of the moderns technological age.

Article 38 E.

Formal education is compulsory up to the age of fifteen years.”

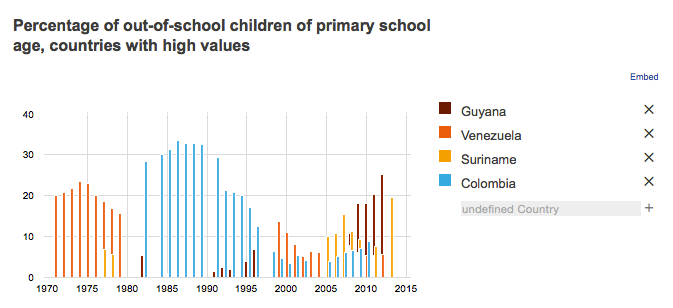

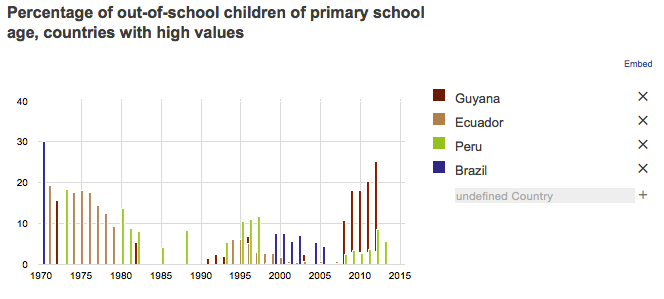

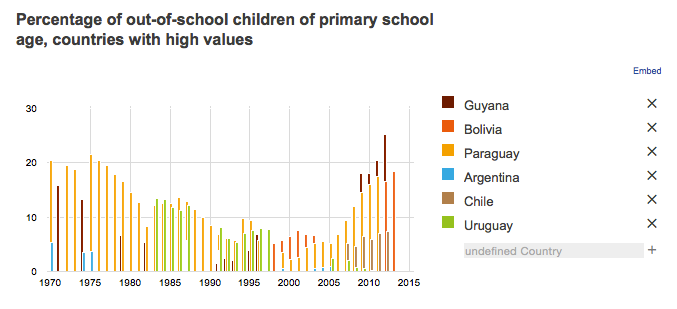

If every citizen, as we see here, should have the right to free education in all different institutional levels, even in non-formal places of education and training, and if every young citizen is compelled to participate in the educational system up to the age of fifteen years, then the preamble’s acknowledgment of the aspiration of Guyanese ‘young people’ depends indeed, to a large degree, on the provision of a national education system. But current regional statistics evaluation seems to demonstrate an opposed enhanced educational fragility in Guyana’s domestic policies, where a growing number of children out-of-school contrasts with the South American tendency of a growing number of school enrollment. The following comparative data taken from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics presents the actual Guyanese situation on primary education:

(Fig. 1, UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

(Fig. 2, UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

(Fig. 3, UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

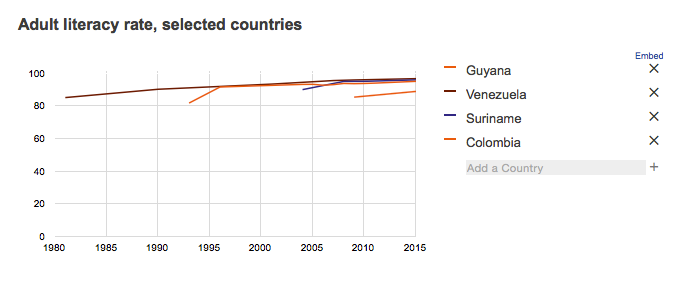

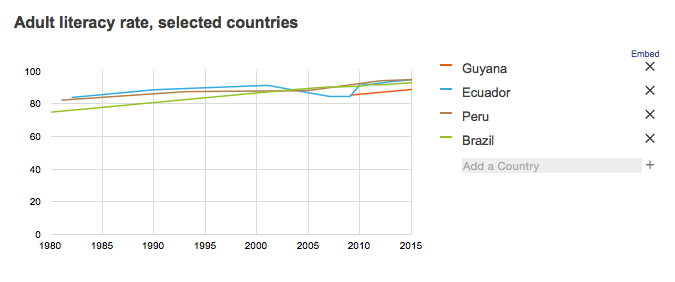

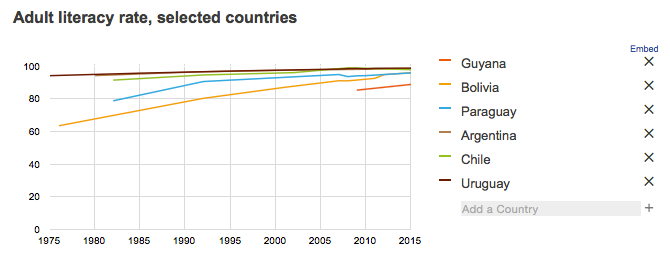

As we can see in those graphics, Guyana remains the South American country with the biggest rate of children out-of-school, what consequently explains its equal biggest rate of adult illiteracy in the region:

(Fig. 4, UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

(Fig. 5, UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

(Fig. 6, UNESCO Institute for Statistics)

While the most part of South American countries present a considerable progress on school enrollment and adult’s illiteracy reduction, Guyana stands at the top of non-school enrollment and adult illiteracy. Its actual rate of out-of-school children is a significant 25.2% of children on primary school age (around 31.8 thousand children). Although it seems to be a big obstacle to be faced by Guyanese public policies, the total number of out-of-school children in Guyana remains significantly low if compared to its giant Brazilian counterpart population. The 31.8 thousand Guyanese children out of school would represent a 0.016% of Brazil’s 198.4 million population. Furthermore, compared to the 4.4% Brazilian rate of out-of-school children, Guyana has an impressive 572% bigger rate of out-of-school children than Brazil for a 26187.9% smaller population.

Obviously, the percentages hide the real poverty behind the numbers (as 4.4% of Brazilian population means 601.2 thousand children out of school), but it is a strong way to demonstrate that social disparities between neighboring countries remains unjustified in the current regional scenario. A common project of a stronger regional political cooperation among South American countries would very likely be profitable to Guyanese domestic scopes and constitutional legal premises. It thus seems insufficient for Guyana’s economic and social prospects to continue de facto a detached country from South American communities, in the solely base of a strong attachment to the Caribbean region.

In fact, Guyanese regional leadership on the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) maintain an ongoing historical strategy of political instability in the South American continent promoted by past Dutch and specially British colonial administrations. Proof of that is that CARICOM founded in 1973, inherits the British West Indies Federation institutional model from 1958. Thus the Guyanese 1966 proclamation of independence, despite all its legal advancements towards a more democratic regime and the successful reform of the 1958 British West Indies Federation into actual CARICOM, have not yet succeeded on an effective change of its regional foreign policy towards another that could sustainably help its structural needs. We have no means to determine exactly what changes could be made to go forward in this direction, and it should evidently be based on a domestic democratic decision, but we can nevertheless point out that its actual detachment from South American political communities is less a matter of national interest than historical inheritance.

The recent independence proclamation in Guyana was an important advancement for regional democracy, but there is still a lack of coherent plans for stronger integration to the closest democratic countries in its surroundings. Contemporary misery has a history, and it can only be changed through democratic cooperation on economic and public policies. For this reason, 2008 has been a remarkable year to the strengthening of a gesture of regional cooperation by the achievement of UNASUR Constitutive Treaty, signed and ratified by Guyana’s government. We hope that its coming 50th years old independence commemoration in 2016 will keep the pace of more alliance with the South American continent, which will depend not only in Guyanese decisions but also in stronger regional alliances (UNASUR Constitutive Treaty aims eg. the establishment of a regional single market and infrastructure collaboration) initiated by neighboring countries.

[1] Where is declared: “§5 (1)Notwithstanding anything in the Interpretation Act 1889, the expression “colony” in any Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed on or after the appointed day shall not include Guyana; … §6 (1)Her Majesty may by Order in Council made before the appointed day provide a constitution for Guyana to come into effect on that day.” Guyana Independence Enacted Act 1966, cf.: www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1966/14/enacted.